When I first heard of the upcoming adaptation of Wuthering Heights, given my recent interest in the book having spent two years studying it, I was extremely excited, hoping that with a modern perspective the story would be done some justice.

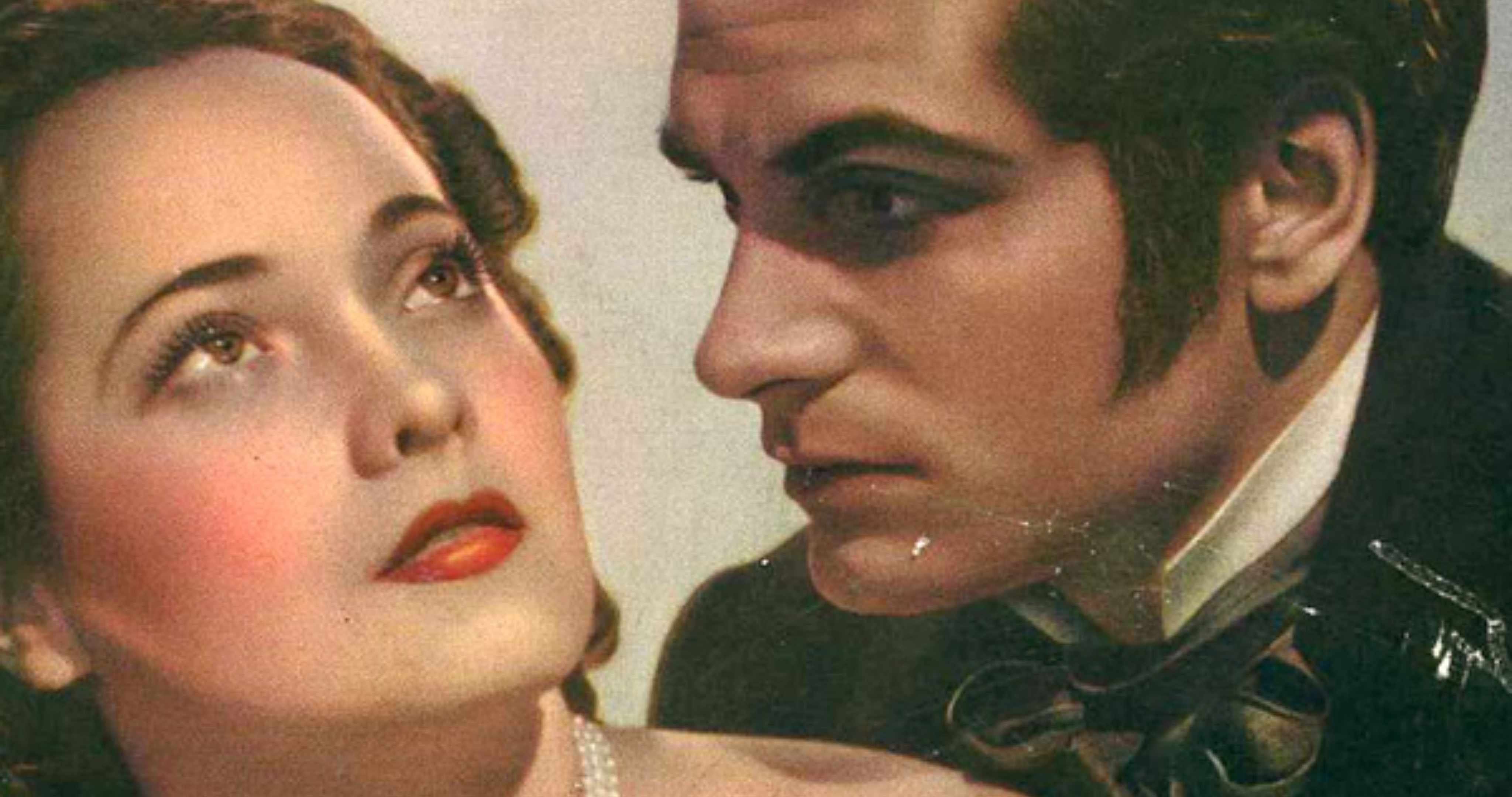

Unfortunately, I was let down before I even watched the trailer. The synopsis alone massively downplays the central conflict of the book, and the trailer missed the mark entirely, painting it as a tragic, old-timey romance with some modernist elements thrown into the mise-en-scene - overall, a massive letdown. Many such adaptations of books are similarly disappointing for die-hard fans, but film adaptations of Wuthering Heights consistently erase the most crucial plotlines, waterdown the characters (especially Catherine), and fundamentally misunderstand the crux of the story. Some of these misunderstandings are more significant than others - therefore, here are some of the most common misconceptions about Wuthering Heights, and how removing them irrevocably alters the story itself:

(Note: For the purposes of this article, ‘Catherine’ will refer to Cathy Sr, and ‘Cathy’ will refer to Cathy Jr.)

1. It’s a romance.

While romance is at the core of a lot of the conflict in Wuthering Heights, it is not the sole focus of the story. In fact, Wuthering Heights can be read as an examination of the cycle of abuse, how ill-treatment breeds resentment and anger, and how children are influenced by their parent’s neglect. The themes of romance are much more intertwined with passion, which in Brontë’s text feels like a depiction of the Romantic poet’s notion of the Sublime, something wild and untameable. Catherine and Heathcliff are obsessed with each other, as Catherine demonstrates in her ‘I am Heathcliff’ speech - but this mutual obsession is their ultimate downfall. By contrast, the next generation of Cathy and Hareton’s love is what makes them stronger - they are not obsessed or consumed by passion, but have a genuine love and respect for each other, which in the end is Heathcliff’s undoing.

2. Heathcliff being black isn’t important to the story.

A common argument is that it doesn’t matter whether the actor playing Heathcliff is black or white - but in reality, it is central to the whole story. Throughout the first volume Heathcliff is abused and mistreated, targeted by Hindley in particular, specifically for his race. He is classed as lower than the servants and given all manner of unpleasant tasks to do, to humiliate and degrade him, even though he voices at times a determination ‘to be good’. This is especially pertinent when Nelly is the first and only person to speculate that his parents may not have been criminals, or destitute - and the film, with Vy Nguyen playing Nelly, could have turned this scene into a moment of solidarity between two non-white people in a country where racism was extremely normalised, adding another layer onto Nelly and Heathcliff’s bond, which persists even past all his terrible deeds.

Racism is a central part of the book, as are the pressures of society on women of the time, as noted below. Really, if this book was released nowadays, it would get slammed for being too ‘woke’.

3. Catherine didn’t like Edgar Linton and didn’t want to marry him.

Personally, one of the most irritating things I found about the film is that Catherine weeps as she makes her famous speech comparing Heathcliff and Edgar Linton. In the book, this conversation is driven by passion, but pragmatic, not tragic - Catherine chooses Edgar due to the societal pressures and conventions of the time, to be the ‘greatest woman of the neighbourhood’, and because in choosing Edgar she thinks that she can help Heathcliff using Edgar’s power and wealth. She also admits that she genuinely does love Edgar, but that it is a different type of love to her love for Heathcliff - she is even happy with Edgar, until Heathcliff returns. It is not a heartbreaking, tragic moment where her hand is forced - she is frustrated, but not crying. In the books, in fact, Catherine rarely cries except on demand - Nelly describes her as ‘vindictive’ and ‘domineering’, and she is just as bad as Heathcliff for being nasty and getting her own way. This is what she really means here - she and Heathcliff are soulmates, because they’re as bad as each other.

4. It’s just a boring tragedy with nothing fun except the romance.

Aside from the compelling characters, astoundingly well put together plot and ghoulish actions of Mr Heathcliff, on my second reading of Wuthering Heights, I discovered to my surprise that it is actually very funny. Lockwood, the hapless narrator, tries to compare himself to Heathcliff’s antisocial nature - ‘A perfect misanthropist’s heaven - and Mr Heathcliff and I are such a suitable pair to divide the desolation between us. A capital fellow!’ - all the while actively pursuing conversation with a man who clearly does not want to speak to him. He then proceeds to be attacked by dogs because he was trying to pet them and ‘unfortunately indulged in winking and making faces’ at them, after explicitly being told not to provoke them, and to be an idiot about Cathy, thinking her pretty.

Nelly Dean, with her dry tone and over-opinionated narration, injects a wonderfully humorous voice to the story, while still telling the tale with the justice it deserves. The characterisation serves as a testament to Brontë’s skill, but this is not all - the increasingly ridiculous scenarios in which characters choose to throw tantrums, the scene where Heathcliff inadvertently saves the life of a baby he hates by just happening to catch him as he walks by, and the exchange where Nelly very calmly and politely tells an inebriated Hindley that she’d prefer to be shot than stabbed with a knife that’s been used to cut herring, all contribute to the humour of a book that critics usually note for being dry, dull and depressing. Even Lockwood’s final attempt at wisdom at the end of the book fails, as he conjectures that the ‘sleepers under the earth’, whom he has just heard are still haunting the moors, cannot be anything but at peace.

5. Heathcliff is just misunderstood.

While the book centres around racism and abuse as the reasoning for Heathcliff’s behaviour, make no mistake - Brontë never goes out of her way to justify Heathcliff’s behaviour with histragic past. She acknowledges instead how Heathcliff’s mistreatment fuelled his decision to keep the wheel turning, to take it all out on the next generation and pass the trauma on once more. Throughout the book, Heathcliff takes a wife specifically to punish her brother and abuse her - holds a young girl hostage simply because of who her parents were - traps, abuses, and, it could be argued, kills his own son - and degrades Hareton for the crimes of his father, taking pleasure in reducing a well-born young man into somebody ‘friendless’ and ‘ignorant’. Not, overall, the actions of a man who is willing to be redeemed.